By Paul Weaver & James Kraynak

For as long as the TOR network has existed one of its primary uses has been the circumvention of Internet firewalls run by oppressive regimes. Iran is no exception to this trend, and in as early as 2011 Iran was the 2nd highest country by TOR users.1 There was even a point where TOR developers and the Iranian government ended up in a technological arms race as the government aimed to block the network while Tor developers simultaneously created new ways to circumvent said blocks, with developers even releasing same-day updates to counteract new restrictions.9 Iran has repeatedly been ranked among the worst countries in the world for press freedom, and it continues to offer little to no opportunity for Iranian citizens to access uncensored media on the Bright Web.11 In recent years, Iran has vastly improved its censorship technology, and Tor developers have been forced to react quickly to continue to provide access to Tor in Iran. Iran has also developed technology that can successfully render VPNs useless, thus ensuring that uncensored Internet can now only be reliably accessed from the Tor Browser.10 Major events, such as protests against the government, have led to spikes in Tor usage by Iranians amidst the government’s attempts to limit access to the outside world. However, Iran has even found ways to shut down access to Tor relays, which has subsequently led to Iran having some of the highest numbers of Tor Bridge users in the world.8 In this blog post we will take an in-depth look at the correlation between Tor usage, both in relays and bridges, to periods of protest and civil unrest in Iran over the last 5 years.

The Tor Browser has multiple methods for accessing the Tor network and the services within it. The first method is using relays, which are nodes that one can connect to to access the Internet through the Tor Browser. However, the list of relays is accessible to anyone, thus any malicious group can easily block access to the open relays, which is exactly what Iran did to limit access to the Tor Browser until late 2019.8 The second method is by using bridges, which are like relays, except that the master list of bridge nodes is not common knowledge and not publicly available. Instead of the master list being published, the computer trying to gain access connects to a hidden node which is also disguised to appear as something other than Tor traffic; therefore, a state seeking to block users from accessing the Tor Browser will have a much harder time stopping bridge users. As Iran got better at restricting access to publicly listed relays, multiple anti-censorship groups have worked to provide information to Iranian citizens on how to access Tor Bridges to bypass government restrictions.7, 10 Iran’s Tor Browser access saw a monumental shift from relay to bridge users around late 2019, after the Iranian government ran its harshest crackdown on the Internet to date.

Authoritarian regimes sought Internet censorship since the inception of the Internet and the revelation of just how powerful the Internet can be as a tool for connection and mobilization. In the age of the Internet, mass movements can erupt more quickly than ever which is extremely concerning for those who wish to control a population, as a result the Iranian government sees almost no benefit in allowing its citizens unfettered access to the Internet. Presently, Iran blocks access to popular social media and media consumption sites, such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), HBO, Netflix, and many more. This need for extreme censorship was further vindicated in the eyes of the Iranian government in the late 2000s by the Arab Spring. During this period the Iranian government saw first-hand the power that social media had on mobilization among everyday citizens. After witnessing the mobilizing power of social media the Iranian state started to enact repressive measures to ensure that the government stayed in power by any means necessary. Furthermore, the Iranian government has seen the mass protests they have decried begin to gain traction across the Internet and social media, leading to their infamous nationwide Internet blackouts, and the need for Iranian citizens to use the Tor Browser to access uncensored Internet. In 2022, during the protests over the death Jina Mahsa Amini, Iran saw notable celebrities, such as actors and athletes, announce support for the protesters over social media.12 This led to the government enacting sweeping crackdowns on social media companies and users who posted in support of the protesters. Iran’s Internet censorship extends beyond just a desire to prevent the outbreak of mass movements, they use it equally as often to cover up atrocities the regime commits against their own citizens. The Iranian government’s unwillingness to negotiate with their disenfranchised citizens and desperation to maintain control leads to the use of violent, and often deadly, force against protesters. This cycle of desperation not only leads to killing but also an equally strong efforts aimed at hiding their actions from their own citizens and the rest of the world. The Iranian government considers it imperative to not only avoid international attention, but a strong impetus to refrain from creating additional motivations among protesters. The result is that the larger and more violent an uprising becomes the more important it is that all contact with the outside world be shut off. The Iranian government has attempted to justify their actions in multiple ways, such as by claiming that the Internet is being used by “enemies of Iran” to bring about the downfall of the nation.16 As a result, the current regime has passed legislation that enables sweeping national Internet shutdowns. The current leadership of Iran has steadily maintained this stance and has further attempted to limit access to many forms of “Western” media and social media in the name of preserving order in Iran.

Tor Usage Since 2018

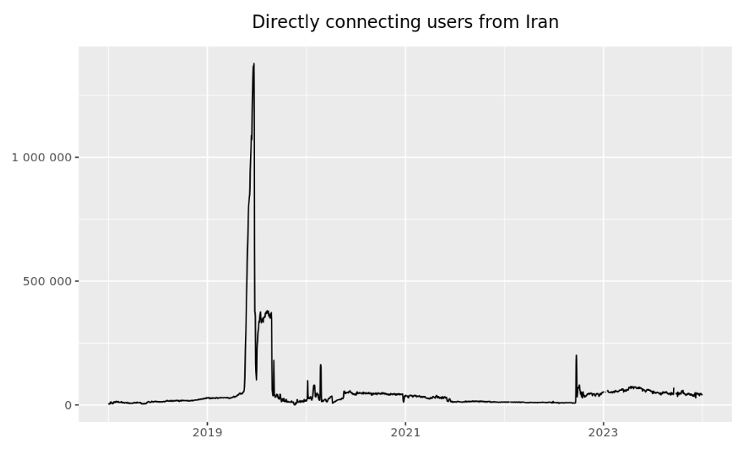

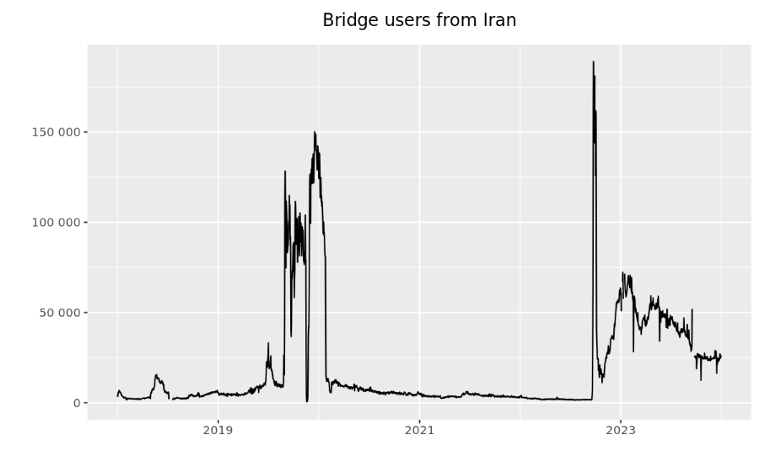

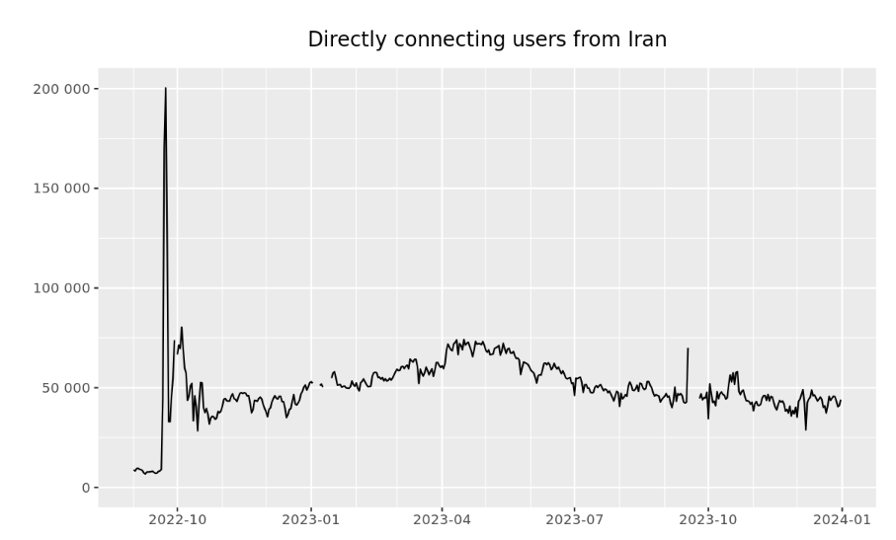

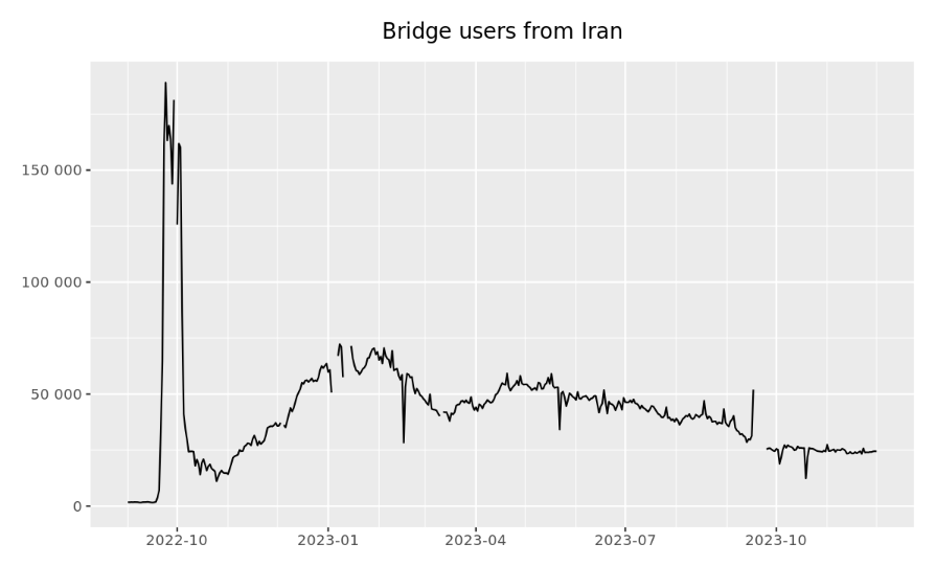

As previously mentioned, there are two main methods of accessing the Tor Browser: Relays and Bridges. In order to notice meaningful trends in their usage data, it is important to first look at their usage as a whole over the period we wish to focus on. The figures shown below chart their usage from the five-year range of 2018 through 2023:

Figure 1: Tor Relay Users in Iran from 2018-2023

Figure 2: Tor Bridge users in Iran from 2018-2023

From the two figures above, it becomes clear that there have been two major spikes across the past five years: one starting in early 2019 and carrying into 2020, and another beginning in late 2022 and carrying into 2023. As we examine those time periods in greater detail a strong correlation emerges between periods of high Tor usage and civil unrest in Iran.

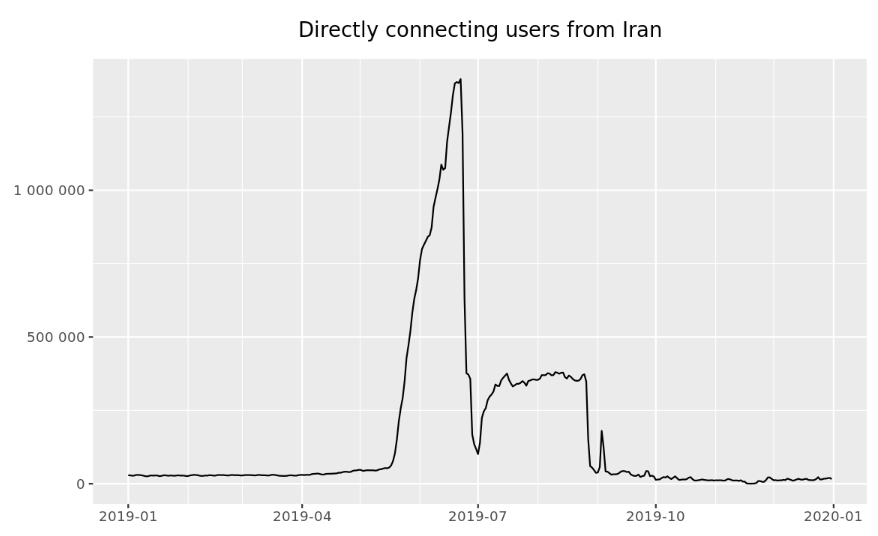

Figure 3: Tor Relay Users in Iran 2019

Interestingly, the biggest spike in Tor Relay users in Iran happened in May of 2019, months before the protests that would break out in November of that year. Up until mid-2019 Iran had been successful in blocking access to Tor relays, until a one-week period where Tor relays became unblocked. During this weeklong period Tor Relay users in Iran rapidly spiked to 1.5 million before the block was reinstated. Soon after relays were briefly unblocked again, with a peak usage of around 25% that of the previous spike before being blocked once again.

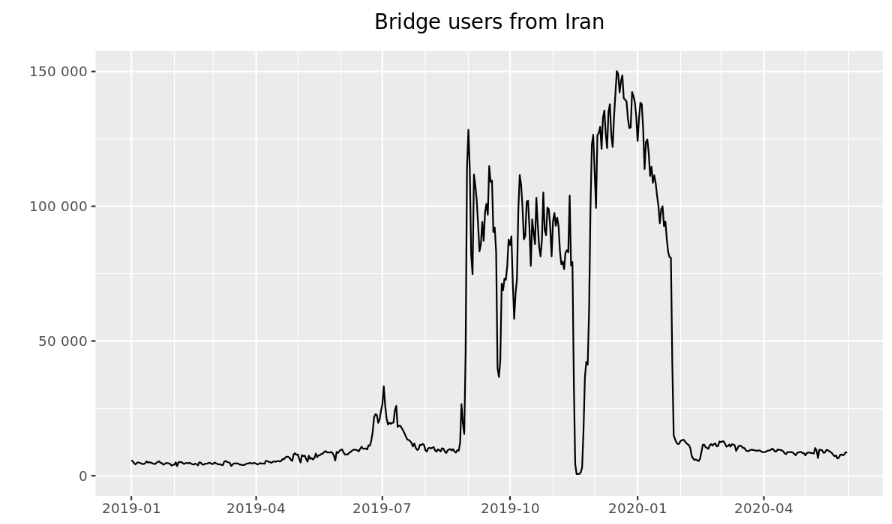

Figure 4: Tor Bridge Users in Iran 2019-2020

Following the restrictions on Tor Relay access many Iranians began using Tor Bridges instead. As previously mentioned, several international media advocacy groups had run campaigns informing Iranians how to use the much harder to restrict Tor Bridges. Unfortunately, there is one way to combat all Tor connections: completely shutting off the Internet. Iran did exactly that in 2019 less than 24 hours after announcing a 300% increase in fuel prices which immediately sparked massive protests across the country.6This occurrence is easily visible in Figure 4 above where one can see the immediate nosedive to zero in the number of bridge users in Iran. These protests were based on an increased desire to remove corruption from the local governments and the economy as a whole. The government claimed that the price increases would be used to support the public with increased funding being put into public works, but many citizens who were suffering as a result of the sanctions against Iran blamed Khamenei for allowing himself and other government run industries to be tax exempt during a period of economic hardship for the rest of the country. There is no better example of the dangers of a population being cut off from the Internet than what happened to the Iranian people during the week-long Internet blackout. The Iranian government cracked down on its isolated population to the tune of over 7,000 arrests and 1,500 of its citizens killed.13It wasn’t until the restoration of the Internet, which saw Tor Bridge usage jump to over 150,000 users, that videos and accounts of what had happened started trickling out to the rest of the world. The information that emerged from Iran was vital for creating an accurate picture of what had transpired. The government had claimed that only about 100 people had died and that protests were few and far between, but first-hand account from the Iranian people told a different story. While the Tor browser had been unable to prevent the violence that occurred against the Iranian people, its use as a tool for sharing what had happened was vital as the resulting international pressure and sanctions on Iran made it clear to the Ayatollah that Iran would be hard-pressed to get away with further complete Internet blackouts in the future. Upon having used the Tor Browser during the course of these protests many people in Iran became aware for the first time of the benefits of using the Tor browser and the average amount of Tor users in Iran was higher in the aftermath. However, many Iranians were also aware of how easily Tor Relays had been shut down and as a result many of them transitioned to using Tor Bridges while abandoning using direct relays, much to the chagrin of the Iranian government.3The number of bridge users once again exploded as protests continued into the early months of 2020. The final series of spikes occurred during the protests due to the Iranian government’s decision to shoot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752; it’s worth noting that these protests were largely populated by students. Interestingly, protests continued throughout 2020, but these protests were held by workers and revolved around working conditions. However, during these protests Tor Browser usage did not spike as it previously had, which points towards a direct correlation between mass student protests and usage of the Tor Browser. After the spikes started to plateau, the average number of Tor Bridge users had increased by around ten to twenty thousand and would remain steady until the protests in 2022 where they would spike even higher than in 2019-2020.

The protests that erupted throughout Iran in 2019 were some of the largest the country had ever seen, but they ultimately paled in comparison to the pure volume and fervency of what would breakout in 2022. The death of Jina Mahsa Amini, a Kurdish woman from Iran’s Kurdistan provence, led to massive protests that lasted for close to six months with flareups occurring again on the anniversary of her death. Jina Amini was arrested in Tehran on September 13th, 2022, for “inappropriate attire”, three days later she fell into a coma and died after having been taken to a “reeducation” center in the city.2 The Kurdish people have been oppressed by the Iranian government for decades and as a result harbored massive amounts of discontent towards the government.2 During Jina’s funeral in her hometown of Saqez, in Kurdistan, emotions boiled over and a massive protest breaks out as the Iranian police fire tear gas at the attendees to try and quell the uprising.

Figure 5: Tor Relay Users in Iran 2022-2023

Figure 6: Tor Bridge Users in Iran 2022-2023

As shown in Figures 5 & 6 above, as protests erupted across the country Tor usage across both relays and bridges skyrocketed as well. As the Iranian government’s control over their population floundered, they once again moved quickly to try and stop their citizens from broadcasting what was happening to the world. The government ramped up attempts to block the Tor browser and other Internet sites, and while they didn’t engage in a full blackout it was the biggest Internet blockage in Iran since 2019.5 Ultimately, the Iranian government was moderately successful as can be seen by the steep drop-offs in Figures 5 & 6. However, following the events of 2019, Iran’s population was more adept at using Tor and a much higher number of both relay and bridge users were able to slip through the cracks. Their efforts were the catalyst for the pure volume of international attention that the Jina Amini protests would receive. The phrases “Woman, Life, Liberty” and “Death to the Dictator” spread like wildfire across Iran and the world as the full scale of the frustration and anger harbored by the Iranian people was put on display. Protests took place across the world in places like Berlin, London, and New York. Additionally, many Iranian celebrities abroad took actions in solidarity with the protesters, often with great personal risk for themselves or their families in Iran. The Iranian National Team refused to sing the national anthem at the World Cup and multiple Iranian women posted videos of themselves burning their hijabs and cutting their hair. Without the Tor browser and the ability for the Iranian people to not only share what was happening to them but also to see the reaction from the rest of the world the protests would likely have had a much smaller international reach than they ultimately did. However, not everything was perfect because of the Tor browser. While hijab laws are now more loosely enforced in Iran, ultimately over 500 people were killed in the protests and over 20,000 were arrested.14 Subsequently, many of those arrested have since been released.14 The Tor browser did play an important role in the 2022 protests, and it is hard speculate on how differently everything might’ve transpired without it.

It’s evident that as civil unrest breaks out across Iran that the people turn to using the Tor Browser as a way of staying in contact with each other and the rest of the world. In the same way that the Iranian people become stronger the harder the government pushes against them, the harder the government tries to block the Tor browser the better its citizens get at accessing it. The Tor browser has been an important tool for the people of Iran as they fight oppression, and it will continue to be one until the day the Iranian people are finally free.

Works Cited:

1. "Bridge User by Country." TOR Metrics February 14, 2024, https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-country.html?start=2017-01-01&end=2023-12-31&country=ir. Accessed February 14, 2024.

2. Berger, Miriam. "At the Center of Iran’s Uprising, Kurds Now Face a Mounting Crackdown." The Washington Post October 18, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/10/18/iran-kurds-protests-mahsa-amini/. Accessed February 14, 2024.

3. Coombs, Casey. "The Dark Web, Iran Style." WIRED December 29, 2019, https://wired.me/technology/iran-dark-web-internet-blackout/. Accessed February 14, 2024.

4. Cunningham, Erin. "More Than 100 Protesters Are Feared Killed in Iran Crackdown, Amnesty International Says." The Washington Post November 19, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/three-security-personnel-killed-in-iran-amid-wave-of-unrest/2019/11/19/af9cbdd6-0a42-11ea-8054-289aef6e38a3_story.html. Accessed February 14, 2024.

5. Mahoozi, Sanam. "'The Internet Is Dead in Iran': Protests Targeted by Shutdown." Reuters September 28, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL8N2ZM0AS/. Accessed February 14, 2024.

6. Qiblawi, Tamara. "Iran’s ‘Largest Internet Shutdown Ever’ Is Happening Now. Here’s What You Need to Know." CNN November 18, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/18/middleeast/iran-protests-explained-intl/index.html. Accessed February 14, 2024.

7. Turak, Natasha. "Hacktivists Seek to Aid Iran Protests with Cyberattacks and Tips on How to Bypass Internet Censorship." CNBC October 5, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/05/how-anonymous-and-other-hacking-groups-are-aiding-protests-in-iran.html#:~:text=Bypassing%20internet%20restrictions,internet%20service%20providers%20(ISPs). Accessed February 14, 2024.

8. O'Neill, Patrick Howell. "Iran Blacklists Tor Network, Knocking 75 Percent of Users Offline." daily dot May 30, 2021, https://www.dailydot.com/debug/iran-censors-tor-75-percent/. Accessed February 15, 2024.

9. arma. "Iran Blocks Tor; Tor Releases Same-Day Fix." Tor Blog September 14, 2011 https://blog.torproject.org/iran-blocks-tor-tor-releases-same-day-fix/. Accessed February 20 2024.

10. Brodkin, Jon. "Tor’s Latest Project Helps Iran Get Back Online Despite New Internet Censorship Regime." ARS Technica February 13, 2012 https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2012/02/tors-latest-project-helps-iran-get-back-online-amidst-internet-censorship-regime/. Accessed February 23 2024.

11. "How the Islamic Republic Has Enslaved Iran’s Internet." Reporters Without Borders October 10, 2022 https://rsf.org/en/how-islamic-republic-has-enslaved-iran-s-internet. Accessed February 23 2024.

12. "Iranian Archer Joins Athletes' Support for Protests." Reuters November 11, 2022 https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iranian-archer-joins-athletes-support-protests-2022-11-11/. Accessed February 23 2024.

13. Staff, Reuters. "Special Report: Iran’s Leader Ordered Crackdown on Unrest - 'Do Whatever It Takes to End It'." Reuters December 23, 2019 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-protests-specialreport/special-report-irans-leader-ordered-crackdown-on-unrest-do-whatever-it-takes-to-end-it-idUSKBN1YR0QR/. Accessed February 23 2024.

14. Gambrell, Jon. "Iran Says 22,000 Arrested in Protests Pardoned by Top Leader." AP News March 13, 2023 https://apnews.com/article/iran-protests-arrested-pardons-mahsa-amini-ae3c45c6bcc883900ff1b1e83f85df95. Accessed February 23 2024.

15. Neufeld, Dialika. "Who Was Jina Mahsa Amini?" Der Spiegel August 8, 2022 https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/an-iranian-icon-who-was-jina-mahsa-amini-a-f6399d1e-589f-436e-8408-3c44861ba035. Accessed February 23 2024.

16. Staff. "Iran Will Restrict Internet Access as Long as Protests Go On." Iran International September 29, 2022 https://www.iranintl.com/en/202209299337. Accessed February 23 2024.