Researching Technology’s Impact on the Human Condition

About the Tech4Humanity Lab

The Tech4Humanity Lab is a transdisciplinary laboratory at Virginia Tech, focusing on the impact of technology on the human condition. Our lab emphasizes issues of human security broadly constituting political, medical, social, economic and environmental securities. The lab utilizes transdisciplinary research, combining practices from political science, law, computer science, humanities, engineering, business, biology, public health, and area studies.

Our mission includes investigating the impact of technological advances on a broad spectrum of security issues. Early research initiatives include surveillance, censorship, data manipulation and misuse, and misappropriation for the purposes of impacting human security across and within multiple disciplines. The lab provides access to resources including High Performance Computing; mobile and IoT technologies; servers, software and simulations for modeling infrastructures; augmented and virtual environments; and a range of digital devices. The lab places concerns of human security at its core and seeks to develop technical- and policy-relevant research that might guide future innovation in ways that minimize negative impacts and enhance a comprehensive approach to technology and human security.

Lab Meetings

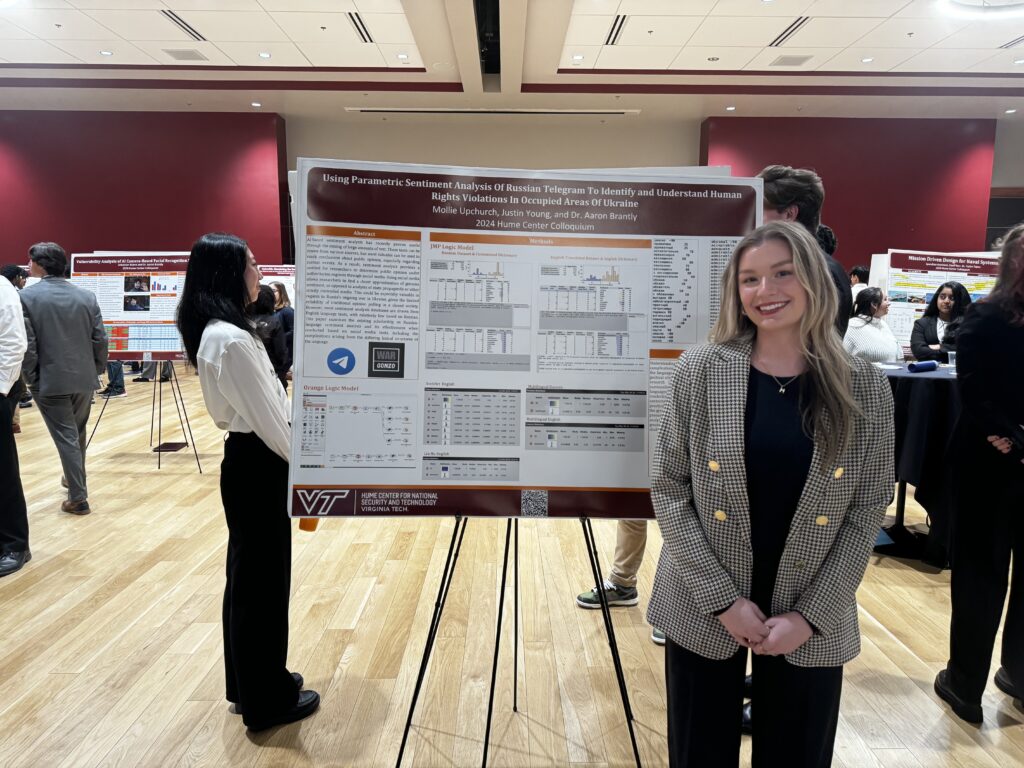

Hume Colloquium Presentations

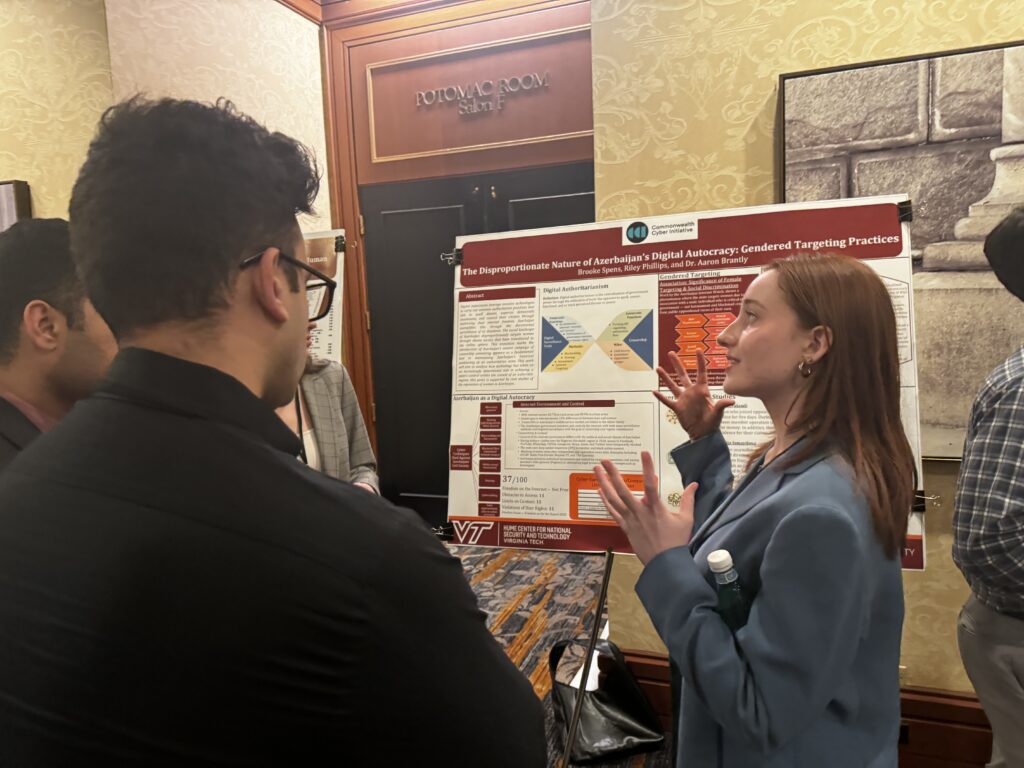

CCI Research Presentations

Aaron F. Brantly – Director

- ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

- HEAD OF RESEARCH, CENTER FOR EUROPEAN UNION AND TRANSATLANTIC STUDIES

- AFFILIATED FACULTY, HUME CENTER FOR NATIONAL SECURITY

- AFFILIATED FACULTY, NATIONAL SECURITY INSTITUTE

Nataliya D. Brantly – Lab Deputy Director

- ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PROGRAM (GIA)

- PROGRAM DIRECTOR, EASTERN PARTNERSHIP RESEARCH PROGRAM CENTER FOR EUROPEAN UNION AND TRANSATLANTIC STUDIES

Latest Blog Posts

-

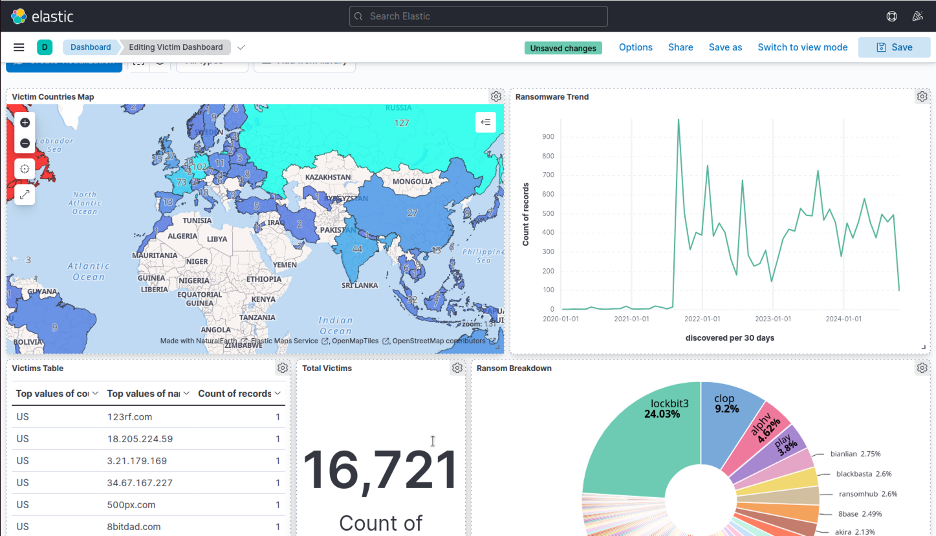

Visualizing Ransomware Data Available in Open Source Repositories

CONTINUE READING: Visualizing Ransomware Data Available in Open Source RepositoriesRansomware poses a persistent threat in the cyber landscape. Over the past four years, there have been more than 19,000 recorded ransomware attacks and leaks, with the number of victims increasing daily. The massive number of attacks in such a short timespan highlights the importance of understanding the tactics employed by ransomware groups.

-

Ransomware and its Effect on Educational Institutions

CONTINUE READING: Ransomware and its Effect on Educational InstitutionsHaleigh Horan and Divine Tsasa Nzita Ransomware attacks have become more common over the past several years and there has been a prominent spike in ransomware attacks against the education sector. As schools and school districts increase their use of technology across their enterprise operations they are increasingly viewed as potential targets with critical resources,…

Tech4Humanity Lab

DROP BY AND SAY HI!

Major Williams Hall 117