By. Ryan Mason & Galen Flanigan

The Tor network provides unparalleled anonymity to its users. Using anonymity features on top of TCP, The Onion Router has proved useful for moderately low-latency tasks such as web browsing (Borinsov and Goldberg 2008). Tor networks operate through a network of thousands of decentralized, independently run nodes across the world. To connect to the network, a computer needs to be running the Tor browser. This browser will randomly connect to its first node, or relay. Each relay in the network only knows the location of the relay or computer immediately preceding and succeeding it. This process completely obfuscates the original computer’s location and makes it appear as if the computer’s IP address is the same as the Tor exit nodes. The connection will travel through three nodes before connecting to a web server- either outside the Tor network, such as a .com or .org top-level domain (TLD), or inside the Tor network- the .onion TLD. These .onion TLDs are known as Onion or hidden services and provide advanced anonymity features like hidden location and IP addresses, end-to-end encryption, automatically generated domain names, and website authentication between the user and the onion service. It can enable sites to be built that publish work without being worried about censorship (Jardine 2018).

Due to the decentralized and anonymous nature of the Tor network, it is extremely challenging for nations to block its traffic (Wells 2020). This is ideal for journalist sites that are blocked or censored in countries. From our analysis, we have found seven news outlets serving 40 languages that provide hidden services to dark web users. While we may not be able to view where traffic is coming from, we can observe how these journalism sites use their hidden services and tailor to different countries. By analyzing the country-specific hidden service news sites and comparing them with Political Repression and Civil Liberties scores of the corresponding countries, we will create a picture of how digital oppression affects journalism on the dark web.

Combing through posts on the Surface Web and databases on the dark web, we found fourteen sites that offered their sites on the dark web. Through our research, we found that seven of these sites were functional: BBC, It’s Going Down, ProPublica, Radio Free Europe, The Guardian, The New York Times, and Bellingcat. The remaining seven news sites were found to be either defunct or utilizing the v2 Tor DNS, which is no longer supported.

The sites we inspected offered a mirror of their international website. A mirror website is a direct, one-to-one copy of another website (“Website Mirror,” n.d.),(“Website Mirror,” n.d.), in this case under an .onion URL. Three of the seven sites (ProPublica, The New York Times, and It’s Going Down) only offered English as the native language of the site, which can be attributed to cost savings as well as where the journalism sites are based. However, highlighting the international site shows awareness from the news outlets of the broad geographic scope of individuals accessing the dark web. According to our analysis, four news outlets offered different languages natively on their website. Bellingcat offered different languages but sent users to their Surface Web pages. Of the seven dark web journalism sites, three news outlets (The Guardian, BBC, and Radio Free Europe) offered localized news on their dark web mirror, and BBC and Radio Free Europe offered their news in languages other than English. This shows an effort from these news outlets to push their information out to people who cannot access it elsewhere. BBC offers its news in 43 languages, targeting most of the Eastern Hemisphere, including Africa, Asia, and Europe. Radio Free Europe offers its news in 27 different languages serving 23 different countries including Afghanistan, Iran, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Russia. On a map, Radio Free Europe serves most of the Middle East as well as most of Europe, especially Eastern European states bordering Russia.

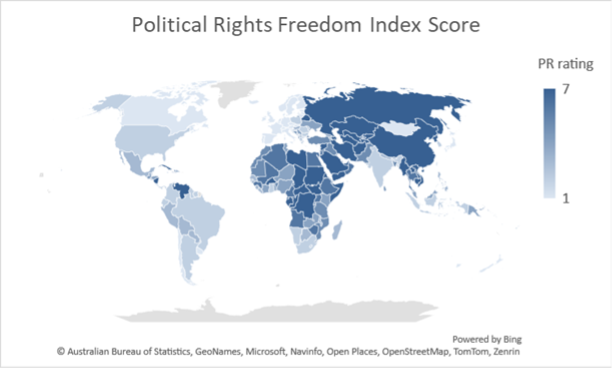

We utilized the Freedom House Index to compare how restrictive or free a given country is. We looked at a country’s political rights rating, civil liberties rating, and freedom status. The Freedom House Index created an aggregate and discrete score for the political and civil rights ratings. This score describes how politically and civilly free the people of a country are, ranked from 1 to 7, with 7 being the least free. Freedom status is a categorical value- listing a country as free, partially free, or not free based on several factors. The world average for political rights was found to be 3.60 (indicating that more countries tend to be more oppressive than free), and the average civil liberties rating was found to be 3.74. In addition, the median for both political rights and civil liberties was found to be 3.0, and the most common value was 1.0 for both political rights and civil liberties as well.

The countries that Radio Free Europe caters to were found to have an average political rights rating of 5.29 and an average civil liberty rating of 4.94. These ratings are both significantly higher than the average for the rest of the world. In addition, the median political rights score was 7 and so was the most common political rights score. The median civil liberties rating was 5, and its most common value was 7 as well. Of the 17 countries that freedom house index had data on 2 were rated free, 6 were rated as partially free, and 9 were rated as not free.

This data indicates that Radio Free Europe caters to areas that are noticeably less free than the world on average, particularly countries that live in the shadow of Russia. This reflects Radio Free Europe’s original mission to fight communism and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Hence its name, Radio Free Europe started out as a radio broadcast, providing local news, music, religion, science, sports, and locally banned literature and music (“The Story of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.Pdf” 2001). The dawn of the internet brought both new opportunities for information sharing and more ways for countries to censor information and monitor individuals, and Radio Free Europe followed suit. They launched a Tor hidden service to continue broadcasting their news to countries that have hindered RFE’s ability to spread its news.

Interestingly, Radio Free Europe no longer reports in much of its original area of focus, especially the former Soviet Bloc states on the Baltic Sea and central Europe. This is because many of these countries had joined NATO in the aftermath of the cold war. In addition, greater American focus in the middle east post 9-11 lead to the expansion of services into Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. In addition is has revamped its services in Russia, paying particular attention to the caucuses and Ukraine since the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea (Johnson 2008). This indicates(Johnson 2008). This indicates how Radio Free Europe follows where the conflicts are, attempting to prioritize the areas where freedom of information is the most important, and could have the greatest effects.

Out of all the countries the BBC serves, 36 of them were in the Freedom House Index’s database. They had an average Political rights rating of 4.67 and a civil rights rating of 4.56. While lower than the average scores of Radios Free Europe, this is still higher than the worldwide average. Of these 36 counties 7 were rated Free, 12 were rated Partially Free and 17 were rated Not Free.

BBC’s broad reach can be attributed, at least in part, to its World Service (formerly known as its Empire Service) (“BBC World Service Launches” 1932). This service was launched in 1932; created to connect the British colonies during World War II, which covered most of Africa’s East Coast, India, Burma, Nigeria, and some of the Middle East. The service proved to be successful, and after Britain decolonized, the service continued. It has evolved into what we see now- over 40 languages provided across Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The Guardian, The New York Times, It’s Going Down, and ProPublica only offer their Tor mirror sites in English. In the physical world, these journalist outlets operate in English speaking countries, but cover international topics. While these sites may not have region-specific offerings like the BBC or Radio Free Europe, improvements in browser-integrated translation services like Google Translate have made the need for region-specific news not as pressing (Perez 2022). The Guardian specifically mentions their United States, United Kingdom, Europe, and Australia Editions. Each of these countries score 1.25 for Civil Rights and Political Rights ratings. These low averages indicate that the Guardian may have a different priority than Radio Free Europe and the BBC in the creation of their dark web mirror.

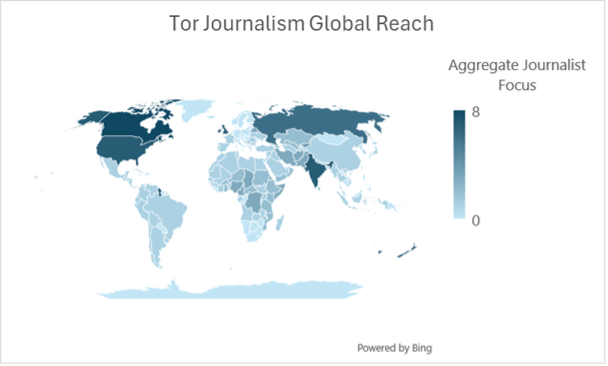

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

The three above charts illustrate our findings. Figure 1, “Tor Journalism Global Reach”, showcases an aggregate of journalist outlets focusing on certain areas. A higher score indicates more focus on a certain country or region. We created a point system for each journalist outlet offering mirror sites on Tor. For every language offered, we gave a point to the country or countries where that language is spoken. The highest journalist focus on this map occurs in The United States, with a score of 7, Canada, with a score of 8, Russia with a score of 6, and India, with a score of 7. The high concentration of focus in The United States and Canada can be attributed to the 7 sites being primarily English-language-based. For Canada, the score is driven higher because a large percentage of the population also speaks French. The other countries on the list, including Russia and India, show an intention from the news sites to push news to these countries in their native tongue, especially when they may be censored. Some of this may be explained by the U-curve observed in Tor usage. In the paper “Tor, What is it Good For?”, Eric Jardine explains that countries with extremely high or low repression show a higher usage in Tor than countries with more moderate repression (Jardine 2018). While there is no clear correlation between the journalist targeting scores and the Political Rights and Civil Liberties scores, we can see that there are correlations based on Radio Free Europe’s and BBC’s global missions. In addition, the mere existence of these dark web sites indicates a larger need for uncensored news in these countries.

Through our research, we discovered several SecureDrop dark websites. These sites were found on the dark web in place of a news outlet’s own dark web mirror site. SecureDrop offers an anonymous way for whistleblowers to report or leak sensitive information through a dark web portal. This appears to be just as common of a technique, if not more common, than mirroring one’s own website on Tor. Large news organizations use these SecureDrop sites, including The Washington Post, The New York Times, Al Jazeera, Bloomberg, and CNN (“What Is SecureDrop?” n.d.).

Since ProPublica created the first major news mirror site the dark web has provided a platform for journalists to circumvent censorship and reach wider audiences globally (Greenberg 2016). Our analysis of major news outlets operating on the dark web found differing approaches based on their target demographics and objectives.

Outlets like Radio Free Europe and BBC offer localized news in multiple languages to provide region-specific information to countries with limited press freedom. Their roots as government-backed broadcasters aimed to counter propaganda likely motivate their continued efforts to promote free flow of information. Other outlets like The Guardian and The New York Times take a more passive approach by simply mirroring their English-language sites. SecureDrop whistleblower portals are also common, indicating a priority on anonymized leaking over localized news access.

Ultimately, the dark web enables journalists to continue their work in the face of digital oppression. However, expanded multilingual and localized offerings could further increase impact. With internet censorship on the rise worldwide, innovative uses of technologies like Tor and anonymity tools will be key for the future of free press.

Bibliography

“BBC World Service Launches.” 1932. BBC. 1932. https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/anniversaries/december/world-service-launch.

Borinsov, Nikita, and Ian Goldberg. 2008. “Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 8th International Symposium, PETS 2008 Leuven, Belgium, July 23-25, 2008 Proceedings.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-70630-4.

Greenberg, Andy. 2016. “ProPublica Launches the Dark Web’s First Major News Site.” Wired. January 7, 2016. https://www.wired.com/2016/01/propublica-launches-the-dark-webs-first-major-news-site/.

Jardine, Eric. 2018. “Tor, What Is It Good for? Political Repression and the Use of Online Anonymity-Granting Technologies.” New Media & Society 20 (2): 435–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816639976.

Johnson, A. Ross. 2008. “History - RFE/RL.” 2008.

Perez, Sarah. 2022. “Google Translate Adds 24 New Languages, Including Its First Indigenous Languages of the Americas.” TechCrunch. May 11, 2022. https://techcrunch.com/2022/05/11/google-translate-adds-24-new-languages-including-its-first-indigenous-languages-of-the-americas/.

“The Story of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.Pdf.” 2001.

“Website Mirror.” n.d. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://support.torproject.org/glossary/website-mirror/#:~:text=A%20website%20mirror%20is%20a,%2Fmirrors.html.en.

Wells, Sarah. 2020. “Who Commits Crime on Tor- A New Analysis Has a Surprising Answer.” Inverse. November 30, 2020. https://www.inverse.com/innovation/a-dark-web-dilemma.

“What Is SecureDrop?” n.d. Accessed February 22, 2024. https://docs.securedrop.org/en/stable/what_is_securedrop.html.