By Jack Bonner and Eric Prindle

Cybercrime is a constantly growing and evolving threat in today’s technological-driven society, compromising governments, businesses, and many people worldwide. Among many strategies cybercriminals utilize for their personal agenda, ransomware attacks have become one of the most prevalent and common types of cyberattack in recent years. Ransomware is a specific type of malware that prevents infected users from accessing their system or personal information until the user delivers a ransom payment to the person or group behind the attack.[1] The malware encrypts the victim's system or data once it has gained access to the device and locks access to the user's personal records and documents until a ransom payment is made. There are several different methods used in ransomware attacks for the threat actor to gain access and utilize the malware needed to encrypt.

Malspam, malvertising, and spear phishing are all methods that threat actors use to gain access to the victim’s computer and files[2]. These methods all share similar attributes in how they are executed. The threat actor may use various methods such as booby-trapped attachments, deceptive advertisements, or infected webpages to exploit the user.[3] These files, webpages, advertisements, or messages may appeal as real and trustworthy, causing the targeted user to click on a link or document that contains the malware which in turns gives it the access it needs. Once the ransomware software encrypts the data or files of the victim, the attacker will see a message demanding them to make a ransom payment to get back their files or date. [4]

Ransomware initially targeted just individual systems and regular people when it was first created. Since then, cybercriminals have realized the full potential of ransomware against businesses, making them the largest target for ransomware attacks.[5] In 2021, 81% of small-medium sized businesses experienced a cyberattack, and 35% were victims of ransomware. [6] In the same year, a hacker group named DarkSide infiltrated Colonial Pipelines computer systems causing Colonial Pipeline to shut down all their systems, resulting in a $4.4 million dollar ransom payment to restore their systems. [7] Widespread panic erupted across the east coast of the United States, highlighting the severe and dangerous implications of ransomware and cyberattacks. There are numerous kinds of ransomware being sold and used as a service on the deep web, with many cybercriminal groups specializing in carrying out and executing ransomware attacks.

Cuba Ransomware Group Profile

The Cuba Ransomware group is one of these specialized cybercriminal groups that have been overwhelmingly successful in their attacks. Cuba ransomware was first discovered in 2019 and rose to prestige in 2022. [8] They have used numerous aliases in the last several years including ColdDraw, Tropical Scorpius, Fidel, and V is for Vendetta. [9] In 2022, Cuba Ransomware collected more than $60 million dollars in ransom from its victims, causing heavy surveillance and attention from the FBI and CISA.[10] Cuba group has found success in utilizing ransomware as a service to profit. They sell and lend consumers and partners their ransomware and in return they acquire part of the ransom that is collected. Organizations in the United States, Canada, and Europe have all been targets of the Cuba group, involving oil companies, healthcare providers, government agencies, and financial institutions.[11] Like most hacking groups, the ransom payments that the Cuba group collects are made through bitcoins or other crypto currencies.

Types of Ransomware Attacks

The heart of ransomware attacks is encrypting files of victims and then demanding payment for the decryption. This simple attack is known as a single extortion tactic. Within the realm of ransomware attacks, there are four different extortion tactics. The second type of ransomware attack is known as a double extortion tactic. This attack is much like a single extortion tactic, but “besides encrypting, attackers steal sensitive information” as well and threaten to publish it online.[12] This is the most popular type of attack by ransomware groups and is the preferred method of the Cuba Group. The third tactic that is used by ransomware groups is a triple extortion, where the ransomware group adds and implements the threat of exposing “the victim’s internal infrastructure to DDoS attacks”.[13] This adds to the pressure of ransomware attacks, because not only will the first attacker have caused damage to the victim’s system and data, but it also adds the element of showcasing vulnerabilities to other attackers. This in turn allows for victims to be targeted multiple times by different attackers.

Lastly, the fourth ransomware model that is used by ransomware groups is a broadcasting tactic, that threatens all of the “victim’s investors, shareholders, and customers” demonstrating that the main cyber infrastructure has been hacked, threatening all users data.[14] This type of tactic is not usually utilized, but it makes it not just that data has been stolen, but it tricks the victim’s population to not trust the head of the administration and cause chaos as fast as possible. An example of this attack is a hack of Bluefield University in Virginia, where attackers hijacked the school’s “emergency broadcast system to send students and staff SMS texts and email alerts that their personal data had been stolen”, and telling students not to trust the school’s statements, as they tried to convince the population that the school was understating the severity of the attack.[15]

Analysis of Attacks

The ransomware group Cuba, is still active as of September of 2023, and they continue to target, much like other ransomware groups, “oil companies, financial services, government agencies, and healthcare providers”.[16] Cuba group is based inside of Russia, and much like the group Conti, their main target nations that have oil companies and financial services are, “North America, Europe, Oceania, and Asia”.[17] In looking at research of executed attacks from the Cuba group, there is a spread of attacks that were targeted at Addison Group, professional consulting firm; Etron, a Taiwanese technology company; KGA, a human resources consulting firm in Massachusetts; and even Iowa State University, along with some police departments across the nations.[18]

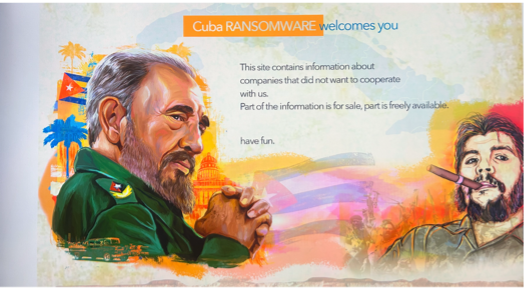

The Cuba Group’s attacks are similar to most ransomware attacks, as they infiltrate computer systems through “phishing campaigns, known vulnerabilities in commercial software, Legitimate remote desktop protocol (RDP) tools, [and] compromised credentials,” and threaten to leak all data.[19] As stated above, the Cuba Group utilized the double extortion tactic, as they conduct ransomware attacks, and threaten to release the victim’s data if they do not pay up. It is because of this tactic that we were able to view and see the type of information that the Cuba Group seized, and from what companies they attacked. In looking at the images below, it can be seen on the Cuba Group’s website, that website visitors are able to view stolen information.[20]

Figure 1: Cuba Ransomware site.

Figure 2: Content stolen that is behind a paywall.

Figure 3: Free and viewable content.

Cuba group’s early attacks in 2021 utilized a “Cobalt Strike beacon-as-a-service on the victim’s network via PowerShell” in conjunction with phishing campaigns to download two files onto the victim’s computer.[21] The first file was called “pones.exe” and was a password collecting software, and the second file was “krots.exe”, which is a program used by the group to cover their track and slow down attribution.[22]

Once the malware had infected the computer and covered its tracks, the ransomware would hijack memory space from the computer to run the ransomware. From here, the ransomware would “then rename the file and add its extension ".cuba" before dropping a ransom note”.[23] With the ransomware attack complete and the note message issued, the victim would have to pay up in hopes that they would get their data back and not leaked on the dark web. It is suggested here by many cyber security officials that victims of ransomware should not pay ransoms due to the decryption sometimes not working, “civil penalties from OFAC for paying malicious cyber actors such as a ransomware group” and continued paying is used by ransomware groups “to justify subsequent attacks and extortion attempts”.[24]

In 2021, Cuba Ransomware successfully infiltrated 49 organizations across critical infrastructure sectors around the world. [25] Cuba ransomware hackers successfully breached Microsoft Exchange servers in 2023 after they discovered vulnerabilities in the system. [26] Businesses and large corporations are not the only victims of Cuba ransomware attacks in the last several years. In 2022, The Ukrainian and Chilean governments were attacked by the Cuba Group.[27] Cuba Group sent phishing emails to government officials with a booby-trapped link to a “new PDF reader,” which actually turned out to be the download for the malware.[28] Inside of Ukraine at this time, the Cuba Group was a threat for everyone as they were not only targeting the national government. They also successfully carried out 27 different attacks on sectors including state and local governments, energy, healthcare, education, and logistical centers. [29] Similar to the attacks on the Ukrainian government and different industries inside the country, Cuba Group also attacked the Philadelphia Inquirer in May of 2023. The group stole and released source code, financial documents, account movements and tax documents, and even caused the Inquirer to shut down business for a period of time. [30]

From January 31st, 2022, through September 30th, 2022, 33 organizations fell victim to attacks carried out by Cuba ransomware.[31] There was no specific industry that was favored or taken advantage of, and the victim organizations belonged to many different sectors. The IT industry had 5 victims, with construction and finance at 4 each. Most other industries that were victims that ranged from energy and utilities to governmental organizations had 2 or 3 victims of Cuba group attacks.[32] Majority of these attacks were on medium sized companies, which were companies consisting of 201-1000 personnel/employees.[33] Although these attacks involved over 10 different countries across the world, over half of the attacks were on industry inside of the United States. [34]

Conclusion

The Cuba ransomware group is just one of the many ransomware groups that plague the internet and the cyber security of corporations, schools, and governments. The unique utilization of the double extortion strategy adds the double threat of having not only your documents locked and lost, but also published on their dark web site. With governments and IT corporations being the main target for the ransomware group, there is some certainty that these companies would pay ransom, as they would want to not have confidential material published on the dark web. This in turn causes for the Cuba ransomware group to continue to attack organizations like this in pursuit of making a profit.

As technology and cyber security increase, ransomware technologies and scams will increase as well. It is up to the human user to stay vigilant and know how to avoid attacks, and if attacked, how to isolate the infected system so it doesn’t spread, and to realize that their data has been lost forever.

References

Avertium, ed. “An In-Depth Look at Cuba Ransomware.” Avertium, May 31, 2023. https://explore.avertium.com/resource/an-in-depth-look-at-cuba-ransomware.

Beek, Kristina. “Cuba Ransomware Gang Continues to Evolve with Dangerous Backdoor.” Dark Reading, September 14, 2023. https://www.darkreading.com/endpoint-security/cuba-ransomware-gang-evolve-backdoor.

BlackBerry, ed. “What Is Cuba Ransomware?” BlackBerry: Intelligent Security. Everywhere. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/solutions/endpoint-security/ransomware-protection/cuba.

CISA, ed. “#stopransomware: Cuba Ransomware: CISA.” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency: CISA, January 5, 2023. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa22-335a.

Freed, Anthony M. “Three Reasons Why You Should Never Pay Ransomware Attackers.” Cybereason. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.cybereason.com/blog/three-reasons-why-you-should-never-pay-ransomware-attackers.

Kirichenko, Alexander, and Gleb Ivanov. “From Caribbean Shores to Your Devices: Analyzing Cuba Ransomware.” SecureList by Kaspersky, September 11, 2023. https://securelist.com/cuba-ransomware/110533/#:~:text=Back%20then%2C%20the%20cybercriminals%20had,government%20agencies%20and%20healthcare%20providers.

Malwarebytes, ed. “All About Ransomware Attacks.” Malwarebytes. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.malwarebytes.com/ransomware.

Mason, Ryan. “Cuba Repository Data Log.” Blacksburg: Virginia Tech: Tech 4 Humanity Lab, 2024.

Trend Micro Research, ed. “Ransomware Spotlight: Cuba.” Security News, December 7, 2022. https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/ransomware-spotlight/ransomware-spotlight-cuba.

Wood, Kimberly. “Cybersecurity Policy Responses to the Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack.” Cybersecurity Policy Responses to the Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack | Georgetown Environmental Law Review | Georgetown Law, March 7, 2023. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/environmental-law-review/blog/cybersecurity-policy-responses-to-the-colonial-pipeline-ransomware-attack/.

[1] Malwarebytes, ed. “All About Ransomware Attacks.” Malwarebytes. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.malwarebytes.com/ransomware.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Wood, Kimberly. “Cybersecurity Policy Responses to the Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack.” Cybersecurity Policy Responses to the Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack | Georgetown Environmental Law Review | Georgetown Law, March 7, 2023. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/environmental-law-review/blog/cybersecurity-policy-responses-to-the-colonial-pipeline-ransomware-attack/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] BlackBerry, ed. “What Is Cuba Ransomware?” BlackBerry: Intelligent Security. Everywhere. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/solutions/endpoint-security/ransomware-protection/cuba.

[9] Kirichenko, Alexander, and Gleb Ivanov. “From Caribbean Shores to Your Devices: Analyzing Cuba Ransomware.” SecureList by Kaspersky, September 11, 2023. https://securelist.com/cuba-ransomware/110533/#:~:text=Back%20then%2C%20the%20cybercriminals%20had,government%20agencies%20and%20healthcare%20providers.

[10] BlackBerry, ed. “What Is Cuba Ransomware?” BlackBerry: Intelligent Security. Everywhere. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/solutions/endpoint-security/ransomware-protection/cuba.

[11] Kirichenko, Alexander, and Gleb Ivanov. “From Caribbean Shores to Your Devices: Analyzing Cuba Ransomware.” SecureList by Kaspersky, September 11, 2023. https://securelist.com/cuba-ransomware/110533/#:~:text=Back%20then%2C%20the%20cybercriminals%20had,government%20agencies%20and%20healthcare%20providers.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Beek, Kristina. “Cuba Ransomware Gang Continues to Evolve with Dangerous Backdoor.” Dark Reading, September 14, 2023. https://www.darkreading.com/endpoint-security/cuba-ransomware-gang-evolve-backdoor.

[18] Mason, Ryan. “Cuba Repository Data Log.” Blacksburg: Virginia Tech: Tech 4 Humanity Lab, 2024.

[19] CISA, ed. “#stopransomware: Cuba Ransomware: CISA.” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency: CISA, January 5, 2023. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa22-335a.

[20] Mason, Ryan. “Cuba Repository Data Log.” Blacksburg: Virginia Tech: Tech 4 Humanity Lab, 2024.

[21] Avertium, ed. “An In-Depth Look at Cuba Ransomware.” Avertium, May 31, 2023. https://explore.avertium.com/resource/an-in-depth-look-at-cuba-ransomware.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Trend Micro Research, ed. “Ransomware Spotlight: Cuba.” Security News, December 7, 2022. https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/ransomware-spotlight/ransomware-spotlight-cuba.

[24] Freed, Anthony M. “Three Reasons Why You Should Never Pay Ransomware Attackers.” Cybereason. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.cybereason.com/blog/three-reasons-why-you-should-never-pay-ransomware-attackers.

[25] Avertium, ed. “An In-Depth Look at Cuba Ransomware.” Avertium, May 31, 2023. https://explore.avertium.com/resource/an-in-depth-look-at-cuba-ransomware.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Trend Micro Research, ed. “Ransomware Spotlight: Cuba.” Security News, December 7, 2022. https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/ransomware-spotlight/ransomware-spotlight-cuba.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.