Azerbaijan’s Newest Tool of Digital Repression: The Disproportionate Spread of Spyware and Surveillance in the Region

By Brooke Spens and Riley Phillips

Abstract

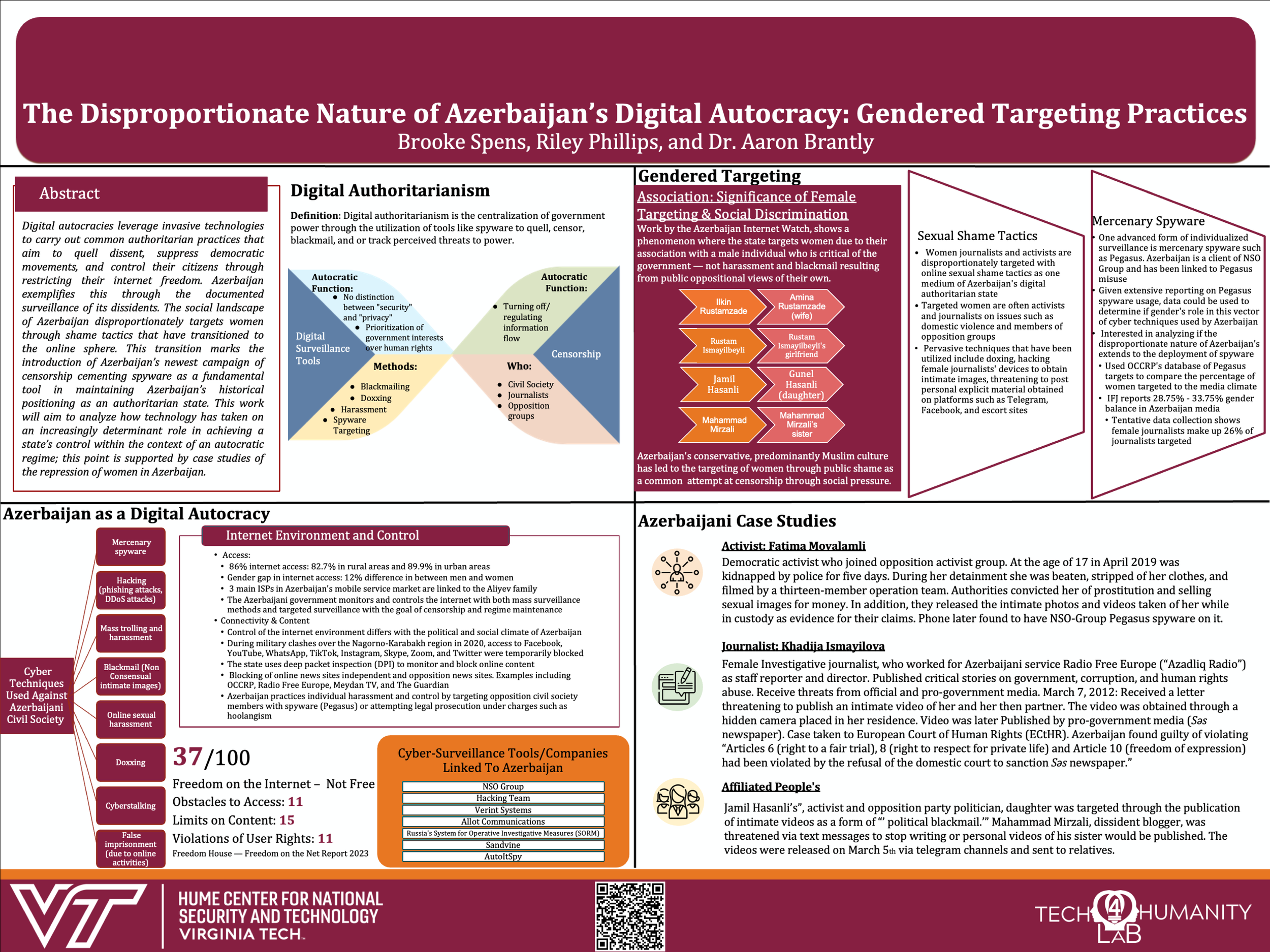

Digital autocracies leverage invasive technologies to carry out common authoritarian practices that aim to quell dissent, suppress democratic movements, and control their citizens through restricting their internet freedom. Azerbaijan exemplifies this through the documented surveillance of its dissidents. The social landscape of Azerbaijan disproportionately targets women through shame tactics that have transitioned to the online sphere. This transition marks the introduction of Azerbaijan’s newest campaign of censorship cementing spyware as a fundamental tool in maintaining Azerbaijan’s historical positioning as an authoritarian state. This work will aim to analyze how technology has taken on an increasingly determinant role in achieving a state’s control within the context of an autocratic regime; this point is supported by case studies of the repression of women in Azerbaijan.

What is Digital Authoritarianism?

Digital authoritarianism is the centralization of government power through the utilization of tools like spyware to quell, censor, blackmail, and or track perceived threats to power. Under a digital autocracy, the balance between security and privacy holds no distinction when it comes to government oversight resulting in instances of abuse and priority of government interests over privacy rights.[1] Digital authoritarianism uses mass and targeted forms of surveillance and censorship to manipulate the online information landscape. The Pegasus Project and Predator Files revealed that spyware plays a key role in maintaining digital authority over a nation through its employment over individuals and in some cases communities.[2] Spyware technology such as Pegasus, Cytrox, and Predator leverage the insecurity of cell phones as targets for collecting valuable data to facilitate the doxing, blackmail, and harassment of perceived dissidents of those in power.[3] In the context of spyware, activists in Azerbaijan face “online harassment, doxing, and blackmail.”[4]Azerbaijan in 2023 received a Freedom House, freedom on the net, rating of thirty-seven out of one hundred classifying it as “not free.”[5] That is one point lower than 2022 which received a total of thirty-eight.[6] Three categories that make up this score include: obstacles to access, limits on content, violations of user rights.[7] These scores reflect an autocratic state through the valuing of government interests over privacy rights.

Azerbaijan as Digital Autocracy

Studies indicate that there are two primary perspectives on the impact and interaction of the internet on authoritarian regimes: one emphasizing its potential for democratization through social networking sites and another highlighting its role of repression in a given region.[8] In the case of Azerbaijan, the government asserts itself as a digital autocracy through its utilization of disinformation and surveillance techniques against civil society. Following the Arab Spring and similar mass demonstrations in the early 2010s, the Azerbaijani government invested heavily in digital surveillance tools from companies such as Sandvine, Verint Systems, Allot Communications, and the notorious spyware developer NSO Group.[9] The surveillance products acquired ranged from Hacking Team’s spyware DaVinci, to the eavesdropping of internet traffic with Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) tools. One example of the implementation of these products included black boxes sold by the telecommunications company TeliaSonera which could be used by Azerbaijani law enforcement to monitor phone calls and internet traffic to identify those who opposed the government on election issues such as the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[10] Autocratic practices in Azerbaijan extend beyond surveillance tactics to efforts in controlling the information flow. The Azerbaijan government strictly controls broadcast media and print content to sow state narratives across all platforms—a behavior that can proliferate in the digital age and transcend sovereign boundaries.[11] Historically, specific techniques used by Azerbaijan included blocking opposition news sites, imprisoning activists, and distributing targeted kompromat with the aim of censorship and legitimization.[12] Control of the internet environment differs with the political and social climate of Azerbaijan; during military clashes over the Nagorno-Karabakh region in 2020, access to Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, TikTok, Instagram, Skype, Zoom, and Twitter were temporarily blocked.[13] The control of internet connectivity is partially enabled through the ownership of three large mobile service companies in the Azerbaijani market. Aztelekom, Azercell, and Azerfon all have ties to the ruling Aliyev family.[14] Subsequent sections will detail how the characteristics of Azerbaijan’s digital autocracy described are disproportionate in nature, with an emphasis on the role of gender in Azerbaijan’s media climate.

Gendered Targeting: Women and Azerbaijan’s Media Climate

Women journalists disproportionately face the effects of Azerbaijan’s digital autocracy compared to their male counterparts, particularly regarding sexual shame tactics on digital platforms. Sexual shame tactics can include practices such as nonconsensual intimate images, or the release of sexually explicit images without the consent of the individual, and online sexual harassment such as sextortion and unwanted sexualization.[15] Due to the media climate in Azerbaijan, the Azerbaijani government, who is the alleged perpetrator of these attacks, has found gendered targeting to be an effective method to censor dissidents in the region. Given the conservative, predominately Muslim environment of the country, the effectiveness of social pressure provoked by the targeting and exploitation of these women has led to the proliferation of these means to further legitimize Azerbaijan‘s authoritarian regime.[16] Datasets compiled using the Azerbaijan Internet Watch (AIW) and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) show the significant targeting of women due to their association with male members of the opposition and journalists.[17] This gendered targeting due to affiliation is an area to be expanded on as this research progresses. Specific examples of women targeted due to affiliation will be covered in forthcoming case studies; however, common features from these cases include the use of the platforms Facebook and Telegram to carry out cyber harassment such as mass trolling and the spreading of kompromat against women.[18] Further analyzing the intersectionality of gender and sectors of digital authoritarianism, data of journalists targeted by NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware showed a ratio of 1:3 female to male journalists targeted. This can be correlated to the International Federation of Journalists report that the gender balance is around 30% of females in the Azerbaijani media.[19] Preliminary findings from this dataset of surveilled journalists demonstrate that mercenary spyware appears proportionate among gender and would indicate that spyware is not an unbalanced gender ratio sector when compared to other practices of Azerbaijan’s digital authoritarian state. Tentatively, it can be concluded through the widespread reporting of Azerbaijan’s cyber harassment and digital surveillance that the state relies heavily on the use of online sexual shame tactics against women to control their media climate. Although the use of digital surveillance is prevalent by Azerbaijan’s regime, from the angle of gendered targeting, sexual shame tactics more commonly affect women journalists, opposition, and associated individuals.

Case Studies

Azerbaijan infamously used sexual shame tactics in an attempt to expurgate the investigative journalist and radio host direction, Khadija Ismayilova. Ismayilova, an Azerbaijani national, has worked as an investigative journalist since 2005 for “Azerbaijani service of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty (‘Azadliq Radio’), as a staff reporter and director.[20]Ismayilova is a critic of the government specifically investigating corruption between 2010-2012 and working as the “regional coordinator for the [OCCRP],” involved the training of journalists.[21] On March 7th 2012, a threat was made to her explaining that a secret camera in her room had recorded intimate acts with her and her partner and would be made public, March 14, 2012 the video was posted online.[22] The “immoral behavior” was used to reassert state leaders through the defamation of her character. Articles following the videos publication stated that it was “’not surprising’” state opposed individuals were involved in “‘sex scandals.’”[23] Sexual shaming tactics reinforce the moral soundness of the party in power by leveraging socialized promiscuity; often through blackmail, doxing, and invasion of privacy rights using digital surveillance tools. In the European Union Court of Human Rights Azerbaijan was found guilty of violating Article 6, right to fair trial; 8, right to respect for private life; 10, freedom of expression; and Article 41, “‘just satisfaction for the injured party.’”[24] The process of censorship through shame tactics is not unique to Ismayilova. In 2019, Fatima Movlamli an Azerbaijani activist was kidnapped by police for five days.[25] She was seventeen at the time. In custody, a 13-member operation team took off her clothes and beat her in addition to filming her. Operation team’s claims on her involvement in “immoral things” such as prostitution justified her capture. Intimate photos and videos were released on social platforms as promised once Movlamli spoke out about her experience. Movlamli believed that the images released were taken during her kidnapping, but OCCRP learned that she was targeted in 2019 with NSO Group’s invasive spyware Pegasus.[26] This pattern continues to other journalists and activists as well as women affiliated with male activists and opposition group members. Personal trauma and effect cannot be measured from these tactics but the gravity of intimacy and sexuality exploitation implies strong personal, social, and professional consequences. These case studies highlight the prioritization of government interest over individuals' privacy through methods of surveillance and censorship.

Conclusions

Censorship and surveillance tools seek to harass a state’s civil society, activists, and opposition groups, solidifying their status as a digital autocracy through the disillusionment of freedom of expression and press. Autocratic states maintain centralized control of information flow, perspectives, and the extension of power through digital surveillance and censorship practices. Azerbaijan leverages digital surveillance tools like Pegasus but more broadly regulates the broadcast media and print content to maintain state narratives.[27] Spyware regulates dissident actors of the state seeking to reveal corruption and injustice. Spyware attacks were tentatively not found to be applied disproportionately by gender. Sexual shame tactics, however, have shown to be readily applied to female journalists, activists, and affiliated peoples. Through sexual shaming, online harassment, and spyware targeting women experience the dipropionate effects of digital authoritarianism. Sexual shame tactics leverages the conservative cultural climate of Azerbaijan to discredit prominent female voices by spreading explicit images or convicting them of different forms of sex work.[28]Each act of suppression serves to uplift or maintain state-based narrative of power and to de-influence the public from deemed morally ambiguous opposition figures. By calling into question the moral standards of opposition figures, Azerbaijan not only censors' freedom of expression and of press but through public demonstrations (i.e. releasing explicit images) implies that those in power are of the soundest moral standards and therefore should be trusted with censorship and surveillance practices to maintain power. Prospective areas of study include further analyzing barriers of access for female journalists, the effects of surveillance and censorship tactics on women contextually, and how autocratic states like Azerbaijan continue to conduct such abuse.

[1] Papademetriou, G. T. (2023). Disrupting Digital Authoritarians: Regulating the Human Rights Abuses of the Private Surveillance Software Industry. Harvard Human Rights Journal 36, 191–222. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/hhrj36&i=191

[2] Veld, S. in ‘t. (2023). EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT DRAFT RECOMMENDATION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE COMMISSION following the investigation of alleged contraventions and maladministration in the application of Union law in relation to the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-9-2023-0260_EN.html

[3] Papademetriou, G. T. (2023). Disrupting Digital Authoritarians: Regulating the Human Rights Abuses of the Private Surveillance Software Industry.

[4] Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report. (2023). https://freedomhouse.org/article/azerbaijan-government-must-stop-blackmailing-women-journalists-response-criticism

[5] Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report. (2023).

[6] Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report. (2023).

[7] Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report. (2023).

[8] Najmin Kamilsoy and Sofie Bedford, “Digital Authoritarianism and Activist Perceptions of Social Media in Azerbaijan,” August 21, 2023, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Najmin-Kamilsoy-2/publication/373271742_Digital_Authoritarianism_and_Activist_Perceptions_of_Social_Media_in_Azerbaijan/links/64e4822a434d3f628c3f5bcd/Digital-Authoritarianism-and-Activist-Perceptions-of-Social-Media-in-Azerbaijan.pdf.Kamilsoy and Bedford.

[9] Miranda Patrucic Bloss Kelly and Kelly Bloss, “Life in Azerbaijan’s Digital Autocracy ‘They Want to Be in Control of Everything,’” July 18, 2021, https://www.occrp.org/en/the-pegasus-project/life-in-azerbaijans-digital-autocracy-they-want-to-be-in-control-of-everything.Bloss and Bloss.

[10] Bloss and Bloss.Bloss and Bloss.

[11] Karena Avedissian, “Azerbaijan’s Foray Into Digital Authoritarianism: The Virtual World of Disinformation and Repression,” October 31, 2022, https://evnreport.com/magazine-issues/azerbaijans-foray-into-digital-authoritarianism-the-virtual-world-of-disinformation-and-repression/.Avedissian.

[12] Kamilsoy and Bedford, “Digital Authoritarianism and Activist Perceptions of Social Media in Azerbaijan.”Kamilsoy and Bedford.

[13] “Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report,” 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/article/azerbaijan-government-must-stop-blackmailing-women-journalists-response-criticism.

[14] “Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report.”

[15] “Targeted Harassment via Telegram Channels and Hacked Facebook Accounts [Updated March 15] – Azerbaijan Internet Watch,” March 9, 2021, https://www.az-netwatch.org/news/targeted-harassment-via-telegram-channels/.

[16] Giorgi Lomsadze, “Azerbaijan Reporter Wins Sex Tape Case,” January 11, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-reporter-wins-sex-tape-case.

[17]Bloss and Bloss, “Life in Azerbaijan’s Digital Autocracy ‘They Want to Be in Control of Everything.’”

[18] “Targeted Harassment via Telegram Channels and Hacked Facebook Accounts [Updated March 15] – Azerbaijan Internet Watch.”

[19] Mushfig Alasgarli and Dr Jelena Surculija Milojevic, “Gender Equality and the Media: Guide for News Producers in Azerbaijan,” February 19, 2024, https://rm.coe.int/gender-equality-and-media-guide-for-news-producers-in-azerbaijan-eng/168094f616.

[20] (“The Case of Khadija Ismayilova v. Azerbaijan (No. 3))

[21] European Court of Human Rights, “CASE OF KHADIJA ISMAYILOVA v. AZERBAIJAN (No. 3),” May 7, 2020, https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CASE-OF-KHADIJA-ISMAYILOVA-v.-AZERBAIJAN-No.-3.pdf.

[22] Rights.

[23]Rights.

[24] (“The Case of Khadija Ismayilova v. Azerbaijan (No. 3))

[25] Fatima Movlamli, “Fatima Movlamli, Azerbaijani Activist,” July 18, 2021, https://www.occrp.org/en/the-pegasus-project/fatima-movlamli-azerbaijani-activist.

[26] Movlamli.

[27] Avedissian, “Azerbaijan’s Foray Into Digital Authoritarianism: The Virtual World of Disinformation and Repression.”

[28] Movlamli, “Fatima Movlamli, Azerbaijani Activist.”

Bibliography

Alasgarli, Mushfig, and Dr Jelena Surculija Milojevic. “Gender Equality and the Media: Guide for News Producers in Azerbaijan,” February 19, 2024. https://rm.coe.int/gender-equality-and-media-guide-for-news-producers-in-azerbaijan-eng/168094f616.

Avedissian, Karena. “Azerbaijan’s Foray Into Digital Authoritarianism: The Virtual World of Disinformation and Repression,” October 31, 2022. https://evnreport.com/magazine-issues/azerbaijans-foray-into-digital-authoritarianism-the-virtual-world-of-disinformation-and-repression/.

“Azerbaijan Freedom on the Net 2023 Country Report,” 2023. https://freedomhouse.org/article/azerbaijan-government-must-stop-blackmailing-women-journalists-response-criticism.

Bloss, Miranda Patrucic, Kelly, and Kelly Bloss. “Life in Azerbaijan’s Digital Autocracy ‘They Want to Be in Control of Everything,’” July 18, 2021. https://www.occrp.org/en/the-pegasus-project/life-in-azerbaijans-digital-autocracy-they-want-to-be-in-control-of-everything.

Kamilsoy, Najmin, and Sofie Bedford. “Digital Authoritarianism and Activist Perceptions of Social Media in Azerbaijan,” August 21, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Najmin-Kamilsoy-2/publication/373271742_Digital_Authoritarianism_and_Activist_Perceptions_of_Social_Media_in_Azerbaijan/links/64e4822a434d3f628c3f5bcd/Digital-Authoritarianism-and-Activist-Perceptions-of-Social-Media-in-Azerbaijan.pdf.

Lomsadze, Giorgi. “Azerbaijan Reporter Wins Sex Tape Case,” January 11, 2019. https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-reporter-wins-sex-tape-case.

Movlamli, Fatima. “Fatima Movlamli, Azerbaijani Activist,” July 18, 2021. https://www.occrp.org/en/the-pegasus-project/fatima-movlamli-azerbaijani-activist.

Rights, European Court of Human. “CASE OF KHADIJA ISMAYILOVA v. AZERBAIJAN (No. 3),” May 7, 2020. https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CASE-OF-KHADIJA-ISMAYILOVA-v.-AZERBAIJAN-No.-3.pdf.

“Targeted Harassment via Telegram Channels and Hacked Facebook Accounts [Updated March 15] – Azerbaijan Internet Watch,” March 9, 2021. https://www.az-netwatch.org/news/targeted-harassment-via-telegram-channels/.